“If you’re thinking without writing, you only think you’re thinking.” – Leslie Lamport. This insightful quote from the American computer scientist who developed the initial version of the LaTeX document preparation system, has been quite literally put to the test by a recent MIT study.

Titled “Your Brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of Cognitive Debt when Using an AI Assistant for Essay Writing Task,” the study was published on the arXiv preprint platform on June 10, prior to undergoing peer review.

Despite the limitations acknowledged by the authors, the results provide an indication of how over-reliance on AI in writing can reduce the cognitive effort we normally invest in developing ideas.

As large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT become increasingly embedded in everyday tasks, the study raises a crucial question: How might this growing dependency affect our ability to think, reason, and learn?

Study setup: Comparing brain, search engine, and AI

The study, which was conducted in four experimental sessions, investigated the cognitive and neural effects of using an AI writing assistant during an essay-writing task. Participants were divided into three groups: one used ChatGPT, another relied on a search engine, and a third wrote essays using only their brain.

In the final session, the setup shifted: those who had used ChatGPT now had to write without it (LLM-to-Brain group), while the Brain-only group switched to using ChatGPT (Brain-to-LLM group). This allowed the researchers to examine both immediate and residual effects of AI reliance.

A total of 54 participants took part in the study over a period of four months. They were between 18 and 39 years old and came from leading institutions in the Boston area, including MIT, Harvard, and Northeastern.

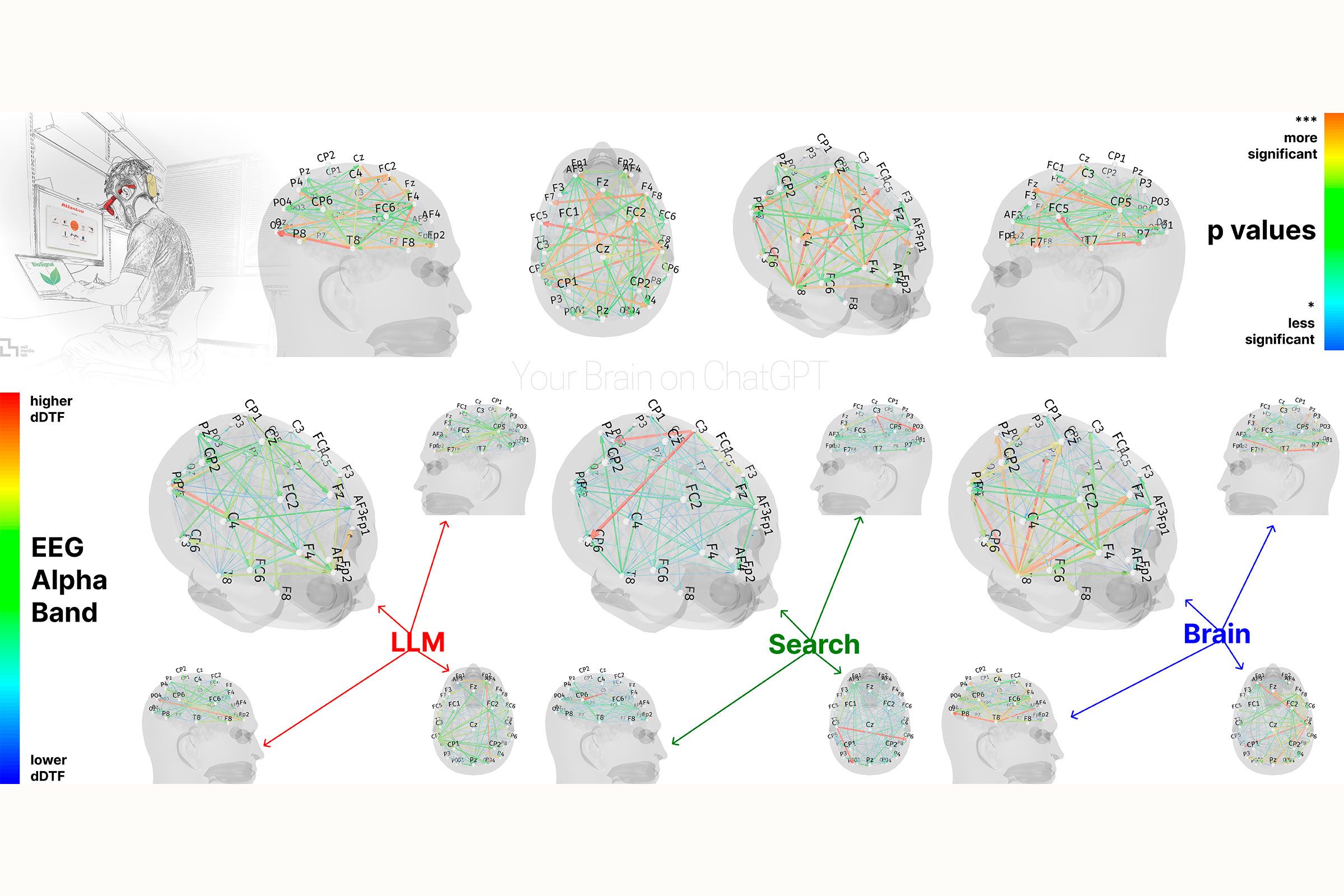

Brain activity was recorded using electroencephalography (EEG) to assess participants’ cognitive engagement and cognitive load during essay writing. Essays were analyzed using natural language processing (NLP) techniques and scored by both human teachers and a specially built AI judge. Post-task interviews assessed participants’ sense of authorship, recall of what they had written, and overall experience with and without AI assistance.

See also: Mindful writing with InstaText

What the brain data revealed

The most striking result was that the use of ChatGPT significantly reduced cognitive effort. EEG data showed that those who wrote without help had the highest neural connectivity, particularly in the alpha and beta frequency bands associated with memory, concentration, and problem solving. The Search Engine group demonstrated moderate engagement, while the ChatGPT group had the weakest connectivity.

These effects were further clarified in the fourth session. The LLM-to-Brain group – those who had originally used ChatGPT – had difficulties when they were asked to write without assistance. Their brains showed reduced activity and coordination. Their essays were flatter, less varied, and filled with generic phrases associated with AI-generated texts. They also had trouble recalling their writing.

Conversely, the Brain-to-LLM group showed increased engagement when switching to ChatGPT. Their prior experience of thinking through essays independently may have enabled them to more actively evaluate and refine the suggestions generated by the AI. Their neural activity spiked across multiple frequency bands, suggesting that using AI tools to rewrite an essay – after having previously written it without help – triggered more extensive and coordinated brain network activity.

See also: How to make your writing sound more natural

Cognitive load and the cost of convenience

These findings align with Cognitive Load Theory, developed by John Sweller, which distinguishes between intrinsic, extraneous, and germane cognitive loads. While ChatGPT reduces extraneous load by simplifying tasks, it can also lower germane load – the type of cognitive effort necessary for deep learning and memory formation. Simply put, the easier it becomes to write with AI, the harder it becomes to actually learn and remember.

The convenience of ChatGPT can mask this cost. Participants who relied on it wrote faster and with less friction, but they often produced more generic content. They also felt less connected to their work, reported lower satisfaction, and had difficulty remembering specific content. In contrast, the Brain-only participants produced essays with greater lexical variety, originality, and coherence – hallmarks of deeper cognitive processing.

Impaired ownership and originality

The NLP analysis revealed another issue: homogeneity. Essays written with ChatGPT followed similar structural and thematic patterns, regardless of the writer. Named entities, n-grams, and topical structures showed a clear lack of variety. Human evaluators confirmed that while the AI-assisted essays were technically correct, they lacked voice, depth, and nuance.

The participants themselves confirmed this in the interviews, with many in the LLM group reporting a low sense of ownership over their essays. This sense of detachment was accompanied by poor recall – even shortly after writing.

Cognitive debt: A new kind of mental fatigue

The concept of cognitive debt emerged clearly in the LLM-to-Brain group. Cognitive debt refers to the gradual accumulation of mental shortcuts and reliance on external aids that limit an individual’s ability to engage in deep critical thinking and problem solving.

After three sessions of AI-assisted writing, participants found it difficult to think independently when ChatGPT was taken away. Their essays showed diminished structure, clarity, and energy. It’s as if their mental muscles had atrophied.

This suggests a long-term cost to short-term efficiency. When we offload too much of the writing process to AI, we don’t just lose fluency – we risk losing the very ability to reason and communicate clearly on our own. Cognitive debt builds up slowly, but its effects can be profound.

See also: Self-editing: Simple tips to improve your own writing

Broader implications for learning and work

The researchers argue cautiously but insistently for balance. While LLMs streamline the writing process, they can also suppress reflection, critical thinking, and mental modeling. In other words, they make it easier to write answers – but harder to formulate questions.

When tools generate prose that sounds reasonable, users may become passive and accept the output without analysis. Over time, this could lead to algorithmic echo chambers in writing – where computer programs repeatedly show similar ideas or styles, limiting exposure to new or different thoughts. These subtle but powerful filters influence not only how we write, but also what we think.

Limitations and the path ahead

Like any early-stage research, this study has its limitations, as acknowledged by the authors themselves. It focused on a specific demographic, a single tool (ChatGPT), and a single type of writing task. It used EEG rather than more detailed neuroimaging. And no sub-processes such as planning or editing were isolated. Nevertheless, the study provides an important indication of how AI could reshape the human experience of writing.

The authors advocate for more diverse and expansive studies across different writing tasks, modalities (including speech and audio), and participant groups. They also emphasise the need for writing samples that are not influenced by LLMs – to preserve individual voice and measure genuine skill in an age of algorithmic assistance.

Writing is thinking – And that matters more than ever

Ultimately, this study does not criticise artificial intelligence, but underlines an important insight: writing is a way of making thinking visible. If intentional writing declines, deep thinking may also diminish. LLMs can be powerful tools – effective when used as collaborators rather than crutches.

Enhancing writing and cognitive skills with InstaText

As the MIT study shows, the key to maintaining and strengthening cognitive engagement in writing is active participation – not passive reliance on AI-generated text.

InstaText, an advanced editing assistant, embraces this principle by offering real-time interactive feedback that encourages users to think critically and make conscious editorial choices.

InstaText uses advanced language technologies, but not generative AI, and focuses on improving readability, clarity, language accuracy, and more through contextual suggestions that the user can accept or reject.

This collaborative editing process helps users refine their voice and develop stronger writing skills over time, turning revision into an opportunity for deeper cognitive engagement.

See also: How InstaText improves writing and cognitive skills

InstaText does not replace the writer’s thinking, but acts as a supportive partner to help you improve both your writing and your critical thinking skills. For those who want to enhance their writing while remaining actively involved in the creative process, InstaText offers an intelligent, effective solution.

If you are new to InstaText, you can start with the Free plan to see how it improves clarity, readability, word choice, language accuracy, and more across multiple languages, with high-precision edits. If you already use InstaText, explore our blog for practical tips on getting more out of your editing experience.

“InstaText is a great tool! I use it to improve English texts such as articles, projects and abstracts for conferences. The tool provides very useful suggestions that help me to translate the text to a professional level so that no additional review by “native speakers” is required. The time and money savings are obvious. I highly recommend it!”

— Dr. Janez Konc, Senior Researcher

“I am a translator and proofreader by profession and have tried many editing tools. It’s not an exaggeration to say that all the other apps I’ve used so far don’t come close to InstaText. It is literally innovative and revolutionary and has taken the editing game to a new level, leaving other competitors in the dust.”

— Dr. Ghodrat Hassani, Researcher in Translation Studies

“This tool is outstanding, exceeded my expectations. I’m used to using Grammarly but InstaText is a more thorough tool and comes up with much better suggestions for rewrites. A game changer for editing.”

— Stephan Skovlund, Business Consultant